Gender Equality ≠ Gender Neutrality: When a Paradox is Not So Paradoxical, After All

Artist credit: Brianna Weir, 2019

Author: Nicole Noll

What makes for a “gender equality paradox” in STEM? Stoet and Geary analyzed gender equality and residents' attainment of tertiary degrees in STEM fields in 67 countries, and found that the gender gap in STEM degrees is smaller in countries that score lower on the Global Gender Gap Index (GGGI) and larger in countries that score higher on the GGGI.1 They interpret this as evidence that gender-equal countries are contexts that “exaggerate” sex differences in individuals’ choices to pursue STEM study at the university level. Stoet and Geary call this finding a gender-equality “paradox” in STEM because it runs counter to their intuition that women and men will become more similar as they become more equal.

Stoet and Geary’s apparent surprise at their finding reflects what Maria Charles and her colleagues have dubbed the “degendering” assumption.2 The idea behind this naïve view—which is not consistent with what gender theory predicts—is that as a country comes closer and closer to women and men experiencing equal outcomes in areas like literacy, life expectancy, education, and representation in government, gender differences in personalities and preferences will disappear.

This post explains why this assumption is unfounded, drawing on research from my field, social psychology. Societies with high scores on gender equality measures should not be assumed to be gender-neutral. This is for three reasons, which are broadly appreciated in the social science literature on gender:

- persistence of gender stereotypes and norms despite formal equality,

- persistence of gender inequality in some domains (e.g., political empowerment) even as there is high gender equality in others (e.g., health and survival), and

- persistence of gender inequality in some demographic groups (e.g., race, class) even when others have achieved gender equality and/or when measures of overall gender equality are high.

For these reasons, social scientists do not expect nation-level measures of gender equality to predict the degree of similarity between women and men on traits, preferences, behaviors, etc. From the perspective of expert research on gender in psychology and other social sciences, findings such as Stoet and Geary’s (even if true3—we raise questions about their data4 and inferences5) are neither surprising nor a “paradox.”

Gender stereotypes and norms

Stoet and Geary interpret a country’s GGGI score as an indicator of gender attitudes and stereotypes in that culture. For example, they claim that, “gender-equal countries are those that give girls and women more educational and empowerment opportunities and that generally promote girls’ and women’s engagement in STEM fields.”1 But gender equality measures like the GGGI are comprised of indicators such as literacy rate, representation in elected office, and participation in the paid labor force—not indicators of norms, attitudes, or stereotypes about gender within a country.6

Understanding gender norms and stereotypes is critical to understanding why gender equality and gender neutrality are not the same concepts. Norms, attitudes, and stereotypes about gender give people information about what is typical and/or desirable in their social context and influence their preferences, beliefs, and behavior. Psychological research has repeatedly demonstrated that gender stereotypes and norms matter for how people conduct their lives and that they contribute to gender differences, and that gender stereotypes and norms are robust even in societies with high gender equality.

We learn about gender early. Children become attuned to gendered information by 9 months of age, associating women’s voices with women’s faces and men’s voices with men’s faces.7 Differential association of colors, objects, traits, emotions, and behaviors with women and men expands rapidly from that point as individuals age and accumulate social experience.8 As social animals, fitting in with our group is important9 and children use their developing knowledge of gender to guide their own behaviors and police those of others.10

In the United States, stereotypical beliefs about gender are related to a wide variety of consequences for women and men.11 Identical achievements, behaviors, credentials, and work products/performances tend to be evaluated more positively when presented as belonging to a man vs. a woman.12 In science specifically, men are seen as more competent, which garners them more job opportunities, mentoring, and higher pay.13 And these are the gender beliefs we are aware of and can consciously reflect upon when we are so motivated. Gender stereotypes also operate outside of our conscious awareness.

Attitudes: Explicit vs. implicit

The psychological study of attitudes goes back to the early days of the field,14 with much of the research focusing on people’s self-reports of their beliefs, that is, their explicit attitudes. Since the mid-’90s, social psychologists have been investigating attitudes that are outside people’s conscious awareness: their implicit attitudes.

| Explicit attitudes | Implicit attitudes | |

| Available to consciousness? | Yes | No |

| Subjective experience? | Known and readily claimed as “my beliefs” | Unknown (without research tools) and often rejected as foreign, “not me/mine” |

| How measured? | Directly, often by self-report | Indirectly, often by reaction time |

| Concern/shortcoming | Deceit, self-presentation | When and to what extent they matter |

Why (and in what contexts) do implicit attitudes matter?

Taking implicit attitudes into account is important because even if we hold egalitarian beliefs, we may still have sexist implicit associations that may influence our behavior.15 As an example of how implicit bias likely matters for women in STEM, consider the finding that faculty in Biology, Chemistry, and Physics at six highly-ranked research-intensive universities in the United States rated a male applicant for a lab manager position as more competent and hirable than a woman with an identical CV, proposed a higher starting salary for him, and offered him more mentoring.13 This hiring scenario highlights how implicit attitudes about gender and science continue to have repercussions for women (and other folks, though in different ways) in the United States, a fairly high-GGGI country.

In many situations, our behavior aligns with our explicit beliefs, but in others, such as when we must act quickly or are distracted, our behavior tends to be more aligned with our implicit attitudes. For example, I might review the applications of candidates for a lab manager position while simultaneously keeping a pot of pasta from boiling over, so my attention would be switching back and forth between these tasks. Or I might read an application during a few minutes of down time between teaching class and walking to a meeting, rushing to finish it in order not to be late. In both of these situations, it would be more likely for my impression of the applicant to be influenced by my implicit associations, whereas if I considered the applications when I had more time and was able to devote my full attention to the task, my implicit associations would likely be “overridden” and my impression of the applicants would be more aligned with my explicit attitudes.

Implicit attitudes also influence behavior when the potential relevance of stereotypes isn’t obvious. For example, if I’m considering a group of potential lab managers, the presence of both female and male candidates can serve as a cue to consider whether my evaluation of their applications is being influenced by stereotypes about gender and science. However, if I’m evaluating a single candidate (as sometimes happens when applications get distributed amongst members of a lab or hiring team), that cue is absent. In such a case I’m focused on the merits of the candidate’s application and not considering that the associations I have with women, which may include their aptitude and/or competence in science, might be tinging how I evaluate her credentials and accomplishments.

Implicit associations leak into our interactions

Automatic behavior is more closely related to implicit attitudes than is deliberate/intentional behavior.16 Much of our nonverbal behavior is automatic, guided by cognitive processes that lie outside of conscious awareness.17 For example, we do not (usually) choose when to smile, blink, squirm, tense up/relax, etc. And yet people who observe and interact with us are attuned to these nonverbal behaviors and are influenced by them.18 Thus, we may be sending mixed signals via our words and actions while being unaware that we are doing so.

For example, in interviewing the lab manager candidates, my verbal communication with them may be very similar—I ask them the same questions, follow-up on their responses, etc.—but my nonverbal behavior may be consistent with my words or it may be inconsistent with them, thereby conveying varying levels of engagement or encouragement across candidates. When verbal and nonverbal signals conflict, people tend to put more stock in the nonverbal message,19 infer that the communicator is being deceitful,20 and like the communicator less.21 Thus these interactions may leave candidates with quite different impressions of how the interview went, their likelihood of being offered the job, and whether they would accept the position if an offer were made.

Even strictly verbal communications can reflect implicit biases. A study of parents’ interactions with children at a California children’s museum found that parents explain science to boys more often than girls, despite girls and boys being equally interested and initiating engagement with exhibits to the same degree.22 Interestingly, other kinds of parental speech observed in this context did not show this difference, as parents instructed girls and boys how to manipulate the exhibits to the same extent and were equally likely to reference the information in the exhibits to girls and boys. The difference in explaining science to girls and boys suggests that parents’ expectations about their children’s interests and proclivities are guiding their behavior in this context. It is worth noting that the sample for this study consisted of people who chose to take their children—both girls and boys—to a science museum, i.e., it’s likely that their explicit attitudes are egalitarian when it comes to aptitude for STEM, so their differential engagement with their girls vs. their boys is likely unconscious.

Pervasive, persistent, and problematic

By 9 years of age, German girls associate math more strongly with boys than with girls and prefer language arts to math, and these implicit math-gender stereotypes are more related to girls’ interests and achievement than are their explicit beliefs.23 By the time they reach college age, young adults have been steeped in gendered messages so thoroughly that they are processed outside of awareness and their influence often goes unrecognized.

Research conducted with college students in the United States found that students’ feelings of belonging and interest in fields of study or careers are influenced by subtly-gendered messages, such as the objects in a classroom or student club hangout space.24 Cheryan and colleagues found that replacing masculine-coded objects like computer parts, Star Trek posters, and science fiction books with neutral objects like water bottles, nature posters, and lamps resulted in female college students indicating as much interest in studying computer science as their male peers. They concluded that objects reflecting masculine stereotypes of computer science sent a message about who was expected to be in the space, and that women anticipated that they wouldn’t belong.

Of course, many women pursue careers in STEM in spite of the gender-science stereotypes and various messages they receive about whether such careers are “for them.” Gender-science stereotypes are multifaceted and their relationship to attitudes and behavior is complex. Having a female math professor doesn’t shift female calculus students’ implicit gender-math stereotypes, but it does strengthen their implicit identification with math.25 Female students who identify more strongly with a field of study stereotyped as masculine tend to have weaker implicit gender stereotypes about that field.26

The point here is that STEM fields continue to be associated with men/masculinity and these stereotypes influence if and how individuals engage with these fields across the lifespan. From preschool to college, children are experiencing implicit and explicit messages that STEM is for boys. This means that, in spite of rising scores on gender equality indices, gender continues to influence people’s opportunities, experiences, and outcomes. Gender equality isn’t the same as gender neutrality.

So what are the correlates, at the societal level, of STEM fields being stereotyped as masculine?27 For one, at a country level, implicit gender-STEM bias is related to inequality in math and science achievement between girls and boys.28 This means that the more strongly a country’s residents associate men with science and women with the liberal arts, the larger the achievement gap between 8th-grade girls and boys in math and science. And we know that gender stereotypes about science persist even in countries that are approaching parity on gender-equality indices such as the GGGI,29 meaning that gender-equality as measured in this way is not an indication that a country is gender-neutral.

Variability in gender equality: Domains

The “paradox” interpretation of Stoet and Geary’s finding hinges on the assumption that higher gender equality scores imply gender-neutral environments. The fallacy of this assumption can be exposed by exploring how the domains tracked by gender equality measures vary within a given country. A domain is a field of activity or interest (e.g., an economic sector, such as agriculture; a field of employment, such as healthcare; an occupation, such as teacher). Related domains can be nested within a broader domain (e.g., dentistry and physical therapy are occupations nested within the healthcare field).

First, countries often lack uniformity across domains. Even with gender equality in some domains, it is lacking in others. Second, within a broad domain, say, within an economic sector, there can be vast variation among the many fields of employment within it. The proportion of women vs. men in one field isn’t necessarily predictive of the gender ratio in another field. This variability means that a gender equality metric cannot be taken to characterize domains not included within that metric. Hence, a gender equality metric cannot characterize the gender neutrality of a society.

Variation across subindices

As explained in our post on measuring gender equality,30 composite gender equality measures draw on a small set of indicators of the status of women and men with a country, typically grouping them into subindices. For example, the GGGI is comprised of four subindices: 1) Economic Participation and Opportunity, 2) Educational Attainment, 3) Health and Survival, and 4) Political Empowerment. A country’s scores on each subindex are comprised of quantitative indicators (e.g., for Economic Participation and Opportunity: labor force participation, wage equality, earned income, etc.).31 The subindex scores are combined in order to determine the country’s overall GGGI score.

It can be easy to forget the process of weighting, calculating, and averaging that goes into producing the overall GGGI score, and as a result assume that the status of women and men is uniform across the measured domains. A quick look at the subindex scores for a few countries with similar overall GGGI scores reveals that this is not the case:

Note that Thailand’s scores on the economic, education, and health subindices are all above .75, but its political subindex score is abysmal. As composite measures, the GGGI and other gender equality indices cannot be used as the basis for inferring that a country is gender-neutral.

Variation across domains within subindices

In addition to divergence across subindices, in focusing on a specific subindex, we see that women’s status varies across the domains that comprise it. Here’s a dive into some areas that fall under the umbrella of the GGGI’s Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex.32

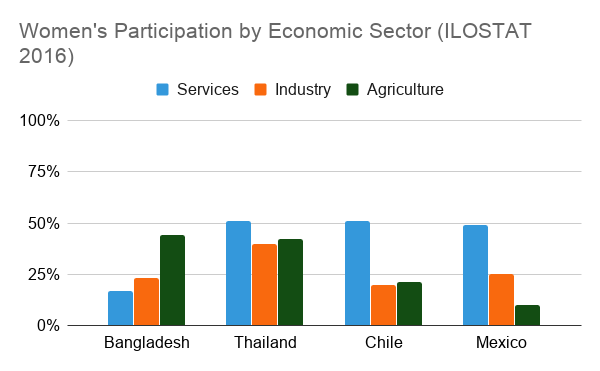

Looking at the three broad economic sectors for the countries examined above, women’s participation across sectors varies within a country. In Mexico, for example, the agricultural sector is 10% women, whereas women comprise almost half the labor force in services industries. Comparing the pattern across these countries, we see that despite their nearly identical overall GGGI scores, the proportion of women vs. men in various economic sectors varies. Variations like these are not reflected in GGGI scores. (The interested reader can interact with these data themselves.33 Note that for both this example and the one in the previous section we’re referencing the countries’ overall and subindex GGGI scores from 2016 to align with most recent available economic sector data.)

In the United States, Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports from 201834 show that women and men are fairly equally represented in management occupations overall (52% women) and in some areas within this domains, such as marketing and sales managers (48% women) and training and development managers (49% women). But these examples of near-parity coexists with dramatic disparities in some management areas. Other management professions are unbalanced in the extreme: only 8% of construction managers and 12% of architectural and engineering managers are women, whereas 73% of public relations and fundraising managers and 78% of human resource managers are. Likewise, in education, women comprise 49% of post-secondary teachers, but 98% of preschool and kindergarten teachers. In the cleaning and maintenance domain, women are 34% of janitors and building cleaners, but 90% of maids and housekeeping cleaners.

Finally, many occupations are skewed toward either women or men. For example, women are 36% of dentists, but 97% of dental hygienists. Women are only 9% of aircraft pilots and flight engineers, but 75% of flight attendants.

| Examples of occupations close to gender parity | Examples of occupations in which women are overrepresented | Examples of occupations in which women are underrepresented |

| Optometrists 46% | Maids and housekeeping cleaners 90% | Security and fire alarm systems installers 1% |

| Biological scientists 48% | Receptionists and information clerks 91% | Automotive body and related repairers 2% |

| Gaming services workers 48% | Hairdressers, hairstylists, and cosmetologists 92% | Carpet, floor, and tile installers and finishers 2% |

| Photographers 48% | Dietitian and nutritionists 93% | Cement masons, concrete finishers, and terrazzo workers 2% |

| Retail salespersons 49% | Childcare workers 94% | Drywall installers, ceiling tile installers, and tapers 2% |

| Statisticians 49% | Medical records and health information technicians 94% | Electricians 2% |

| Advertising sales agents 50% | Secretaries and administrative assistants 94% | Operating engineers and other construction equipment operators 2% |

| Private detectives and investigators 50% | Speech-language pathologists 96% | Structural iron and steel workers 2% |

| Insurance sales agents 51% | Dental hygienists 97% | Logging workers 3% |

| News analysts, reporters, and correspondents 52% | Preschool and kindergarten teachers 98% | Surveying and mapping technicians 3% |

NB: All numbers reflect the percentage of women in the occupation (in the United States for 2018, according to BLS data).

Many fields and careers remain strongly gender-skewed, even in Iceland, the country with the highest GGGI score for gender equality.

The differences outlined above further illustrate the point that a composite gender equality score is a coarse estimate that tells us very little about the specifics of women’s opportunities and participation in a given employment or education sector—such as STEM—but also show that, to the extent the GGGI and similar composite indices do measure gender equality, they cannot be used to infer overall gender neutrality.

Variability in gender equality: Demographic groups

Finally, Stoet and Geary’s conflation of gender equality with gender neutrality erroneously assumes uniformity of outcomes across the broad category of women within a given country, overlooking differences related to socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, age, and other demographic factors. For example, the proportion of women vs. men who are literate in a given country is useful information, but it would be even more informative to know whether the gender ratios are comparable across socioeconomic status. It might be the case that, in high SES families, girls are on par with boys in literacy, whereas in low SES families, girls lag behind boys. Or, when it comes to political empowerment, equal representation of women in government might obscure the fact that male politicians reflect a country’s two main religious groups, but female politicians only reflect one of them.

Sex is an important dimension along which to track people’s outcomes, but sex is entangled with other dimensions of social hierarchy.35 Sexism affects all women, but it does not affect all women in the same ways or to the same degree because it interacts with racism, ageism, classism, etc. For example, a study of Black and white college women found that the Black women participated in STEM majors at a higher rate than the white women did and had weaker implicit gender-STEM attitudes.36 Furthermore, the students’ implicit gender-STEM attitudes partially explained their differing rates of participation in STEM majors. Research on sense of belonging in one’s field of study has shown that women of color majoring in biological sciences reported feeling they belonged at a much lower rate than white women or men of color.37

Women’s outcomes are related not only to their sex, but to other aspects of their personhood. Therefore, it is important to take an intersectional approach and acknowledge that these dimensions are interlocking.

Due to the design of gender equality measures, a high score on one can occlude significant gender inequalities across various social strata within a country. In other words, this is another example of how gender continues to be a factor in people’s opportunities, experiences, and outcomes, meaning that (say it with me now) gender equality is not the same as gender neutrality.

Whither the gender equality paradox in STEM?

The only basis for viewing Stoet and Geary’s finding as a paradox is the assumption that greater gender equality indicates a more gender-neutral society. As demonstrated above, gender equality and gender neutrality are not the same. Due to the pervasiveness and persistence of gender stereotypes related to STEM fields and the multitude of ways in which these attitudes manifest—directly and indirectly—even highly “gender equal” environments cannot be characterized as gender-neutral. Gender gaps persist in some sectors, even in countries that score high on gender equality, and gender gaps vary within a country when examined in concert with other dimensions of social hierarchy. When we recognize that gender-equal on some measures is not synonymous with gender-neutral in stereotypes and attitudes, the paradox falls apart. Better yet, we can identify the places where attention and interventions have the potential to promote greater equality in multiple social spheres, including STEM.

Authorship Statement:

This blog series on the Gender Equality Paradox emerged from collective GenderSci Lab discussions. Each author outlined and drafted their own piece. GenderSci Lab members offered comments and authors integrated these revisions. Brianna Weir developed original artwork for the series. Maria Charles authored and approved the final version of her interview answers and provided images and figures for our use. Tyler Vigen developed a “women in STEM” spurious correlations widget for us and provided permission for the use of his findings in this blog series. Juanis Becerra and Nicole Noll assisted with formatting the blogs for the website. Heather Shattuck-Heidorn oversaw the blog series development, review, and publishing process. For the Psychological Science paper, Sarah Richardson drafted the manuscript. Meredith Reiches and Joe Bruch performed the data analysis. All authors (Richardson, Reiches, Bruch, Boulicault, Noll, and Shattuck-Heidorn) provided critical revisions and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission. Action editor Tim Pleskac shepherded the Corrigendum and Commentary through the peer review process at Psychological Science. We thank the anonymous peer reviewers and Gijsbert Stoet and David Geary for their contributions.

Recommended Citation:

Noll, Nicole E. “Gender equality ≠ gender neutrality: When a paradox is not so paradoxical, after all,” GenderSci Blog, February 17, 2020, https://www.genderscilab.org/blog/gender-equality-does-not-equal-gender-neutrality

Endnotes:

[1] Stoet, G., & Geary, D. C. (2018). The gender-equality paradox in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics education. Psychological Science, 29, 581-593. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617741719

[2] Charles, M., Harr, B., Cech, E., & Hendley, A. (2014). Who likes math where? Gender differences in eighth-graders’ attitudes around the world. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 24, 85-112. https://doi.org/10.1080/09620214.2014.895140; Hendley, A., & Charles, M. (2015). Gender segregation in higher education. Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118900772.etrds0143

[3] Corrigendum: The Gender-Equality Paradox in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Education. (2020). Psychological Science, 31, 110–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619892892

[4] Richardson, S. S., & Bruch, J. (2020, February 12). Gender equality paradox monkey business: Or, how to tell spurious causal stories about nation-level achievement by women in STEM. GenderSci Blog. https://genderscilab.org/blog/gender-equality-paradox-monkey-business-or-how-to-tell-spurious-causal-stories-about-nation-level-achievement-by-women-in-stem

[5] Richardson, S. S., Reiches, M. W., Bruch, J., Boulicault, M., Noll, N. E., & Shattuck-Heidorn, H. (in press). Is there a gender-equality paradox in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM)? Commentary on the study by Stoet and Geary (2018). Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619872762

[6] An exception is the Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI; reviewed in Hawkin & Munck, 2013), which does tap norms as evidenced in various social institutions (via the conceptual dimensions of family law, inheritance, physical integrity, civil liberties, and ownership rights). From p. 816: “Rather, its contribution lies in offering a supplementary measure that encompasses a range of issues pertaining to social institutions and norms that, even if not entirely comprehensive (for example, discrimination in the labor market is not addressed), are ignored by other indices. Thus, the concept of social institutions served as a useful anchor for the SIGI and helps to clarify the meaning of the index.” Hawken, A., & Munck, G. L. (2013). Cross-national indices with gender-differentiated data: what do they measure? How valid are they? Social Indicators Research, 111, 801-838. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0035-7

[7] Poulin-Dubois, D., Serbin, L. A., Kenyon, B., & Derbyshire, A. (1994). Infants' intermodal knowledge about gender. Developmental Psychology, 30, 436. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.30.3.436

[8] Eichstedt, J. A., Serbin, L. A., Poulin-Dubois, D., & Sen, M. G. (2002). Of bears and men: Infants’ knowledge of conventional and metaphorical gender stereotypes. Infant Behavior and Development, 25, 296-310. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0163-6383(02)00081-4; Poulin-Dubois, D., Serbin, L. A., & Derbyshire, A. (1998). Toddlers’ intermodal and verbal knowledge about gender. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 44, 338–354.; Poulin‐Dubois, D., Serbin, L. A., Eichstedt, J. A., Sen, M. G., & Beissel, C. F. (2002). Men don’t put on make‐up: Toddlers’ knowledge of the gender stereotyping of household activities. Social Development, 11, 166-181. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00193; Serbin, L. A., Poulin-Dubois, D., Colburne, K. A., Sen, M. G., & Eichstedt, J. A. (2001). Gender stereotyping in infancy: Visual preferences for and knowledge of gender-stereotyped toys in the second year. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 25, 7-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250042000078; Serbin, L. A., Poulin‐Dubois, D., & Eichstedt, J. A. (2002). Infants' responses to gender‐inconsistent events. Infancy, 3, 531-542. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327078IN0304_07

[9] Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497; Fiske, S. T. (2004). Social beings: A core motives approach to social psychology. New York: Wiley.

[10] Fagot, B. I. (1984). Teacher and peer reactions to boys' and girls' play styles. Sex Roles, 11, 691-702. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00288120; Halim, M. L., Ruble, D. N., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Zosuls, K. M., Lurye, L. E., & Greulich, F. K. (2014). Pink frilly dresses and the avoidance of all things “girly”: Children’s appearance rigidity and cognitive theories of gender development. Developmental Psychology, 50, 1091-1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034906; Martin, K. A. (1998). Becoming a gendered body: Practices of preschools. American Sociological Review, 63, 494-511. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657264

[11] Ellemers, N. (2018). Gender stereotypes. Annual Review of Psychology, 69, 275-298. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011719

[12] Joshi, A., Son, J., Roh, H. (2015). When can women close the gap? A meta-analytic test of sex differences in performance and rewards. Academy of Management Journal, 58, 1516–1545. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0721; MacNell, L., Driscoll, A., & Hunt, A. N. (2015). What’s in a name: Exposing gender bias in student ratings of teaching. Innovations in Higher Education, 40, 291–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-014-9313-4; Proudfoot, D., Kay, A. C., Koval, C. Z. (2015). A gender bias in the attribution of creativity: Archival and experimental evidence for the perceived association between masculinity and creative thinking. Psychological Science, 26, 1751–1761. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615598739; Treviño, L. J., Gomez-Mejia, L. R., Balkin, D. B., & Mixon Jr, F. G. (2018). Meritocracies or masculinities? The differential allocation of named professorships by gender in the academy. Journal of Management, 44, 972-1000. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315599216

[13] Moss-Racusin, C. A., Dovidio, J. F., Brescoll, V. L., Graham, M. J., & Handelsman, J. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109, 16474–16479. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1211286109

[14] Allport, G. W. (1935). Attitudes. In A Handbook of Social Psychology (p. 798–844). Clark University Press.

[15] Nosek, B. A., & Hansen, J. J. (2008). The associations in our heads belong to us: Searching for attitudes and knowledge in implicit evaluation. Cognition & Emotion, 22, 553-594. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930701438186

[16] Dovidio, J., Kawakami, K., Johnson, C., Johnson, B., & Howard, A. (1997). The nature of prejudice: Automatic and controlled processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 33, 510–540. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.1997.1331

[17] DePaulo, B. M. (1992). Nonverbal behavior and self-presentation. Psychological Review, 111, 203–243. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.111.2.203; Niedenthal, P. M. (2007). Embodying emotion. Science, 316, 1002–1005. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1136930

[18] DePaulo, B. M. (1992). Nonverbal behavior and self-presentation. Psychological Review, 111, 203–243. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.111.2.203; Dovidio, J. F., Kawakami, K., & Gaertner, S. L. (2002). Implicit and explicit prejudice and interracial interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 62-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430207084847; Hofmann, W., Gschwendner, T., & Schmitt, M. (2009). The road to the unconscious self not taken: Discrepancies between self‐and observer‐inferences about implicit dispositions from nonverbal behavioural cues. European Journal of Personality, 23, 343-366. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.722

[19] Walker, M. B., & Trimboli, A. (1989). Communicating affect: The role of verbal and nonverbal content. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 8, 229-248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X8983005

[20] Heinrich, C. U., & Borkenau, P. (1998). Deception and deception detection: The role of cross-modal inconsistency. Journal of Personality, 66, 687–712. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00029

[21] Weisbuch, M., Ambady, N., Clarke, A. L., Achor, S., & Weele, J. V. V. (2010). On being consistent: The role of verbal–nonverbal consistency in first impressions. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 32, 261-268. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2010.495659

[22] Crowley, K., Callanan, M. A., Tenenbaum, H. R., & Allen, E. (2001). Parents explain more often to boys than to girls during shared scientific thinking. Psychological Science, 12, 258–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00347

[23] Steffens, M. C., Jelenec, P., & Noack, P. (2010). On the leaky math pipeline: Comparing implicit math-gender stereotypes and math withdrawal in female and male children and adolescents. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102, 947–963. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019920

[24] Cheryan, S., Meltzoff, A. N., & Kim, S. (2011). Classrooms matter: The design of virtual classrooms influences gender disparities in computer science classes. Computers & Education, 57, 1825-1835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.02.004; Cheryan, S., Plaut, V. C., Davies, P. G., & Steele, C. M. (2009). Ambient belonging: How stereotypical cues impact gender participation in computer science. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 1045. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016239

[25] Stout, J. G., Dasgupta, N., Hunsinger, M., & McManus, M. A. (2011). STEMing the tide: Using ingroup experts to inoculate women's self-concept in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021385

[26] Smyth, F. L., & Nosek, B. A. (2015). On the gender–science stereotypes held by scientists: Explicit accord with gender-ratios, implicit accord with scientific identity. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 415. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00415

[27] Cheryan, S. (2012). Understanding the paradox in math-related fields: Why do some gender gaps remain while others do not? Sex Roles, 66, 184-190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0060-z

[28] Nosek, B. A., Smyth, F. L., Sriram, N., Lindner, N. M., Devos, T., Ayala, A., ... & Kesebir, S. (2009). National differences in gender–science stereotypes predict national sex differences in science and math achievement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 10593-10597. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0809921106

[29] Miller, D. I., Eagly, A. H., & Linn, M. C. (2015). Women’s representation in science predicts national gender-science stereotypes: Evidence from 66 nations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107, 631-644. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000005

[30] Boulicault, M. (2020, February 13). Measuring gender equality. GenderSci Blog. https://www.genderscilab.org/blog/measuring-gender-equality-why-the-gggi-is-not-the-right-measure-for-gender-equality-paradox-research

[31] World Economic Forum. (2016). Global gender gap report. Geneva, Switzerland: Author. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-gender-gap-report-2016

[32] Data about the labor force tend to be collected/reported in a manner that reflects the assumption of a sex/gender binary (i.e., that everyone fits neatly into either the category of “woman” or “man”). We disagree, but that’s a topic for a different post.

[33] International Labour Organization. (2016). Employment by occupation. [Data file]. Available from https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/#summarytables

[34] United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2018). Employed persons by detailed occupation, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. [Table]. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/cps/aa2018/cpsaat11.htm

[35] Cole, E. R. (2009). Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist, 64, 170-180. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014564; Combahee River Collective. (1977). Combahee River Collective statement.; Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139-167.

[36] O'Brien, L. T., Blodorn, A., Adams, G., Garcia, D. M., & Hammer, E. (2015). Ethnic variation in gender-STEM stereotypes and STEM participation: An intersectional approach. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21, 169-180. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037944

[37] Rainey, K., Dancy, M., Mickelson, R., Stearns, E., & Moller, S. (2018). Race and gender differences in how sense of belonging influences decisions to major in STEM. International Journal of STEM Education, 5, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-018-0115-6