Explainer: The Limitations of Case Fatality Rates for Measuring Sex Disparities

By Annika Gompers

In a new commentary just out in Women’s Health Issues, the GenderSci Lab examines the limitations of case fatality rate (CFR) as a metric for studying sex disparities in COVID-19 outcomes.

CFRs have been widely cited as demonstrating sex differences in COVID-19 outcomes. In June 2020, the European Commission stated that “COVID-19 related mortality risks are of particular concern for men as the case fatality rate is higher among men for all age groups.” Reports have continued to emerge that CFR is higher among men than among women, and most discussion around this observed pattern has attributed the disparity to biological sex differences in genetics and hormones. But because CFRs are calculated by dividing the number of deaths by the number of confirmed cases of a given disease (in this example, COVID-19), there is an important limitation to comparing CFRs by sex -- if men and women aren’t tested at similar rates, the number of confirmed cases could be wildly skewed in one sex compared to the other.

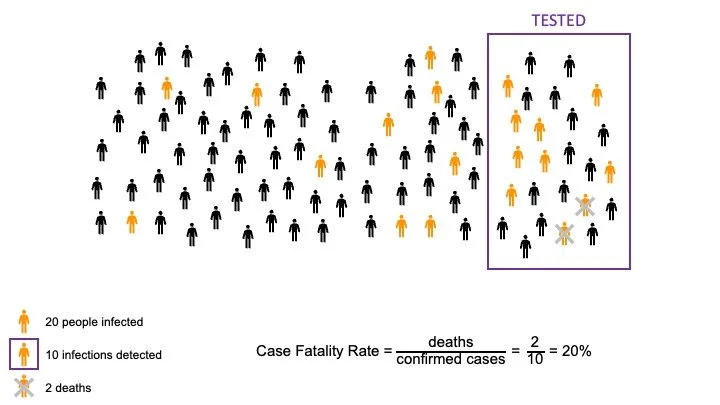

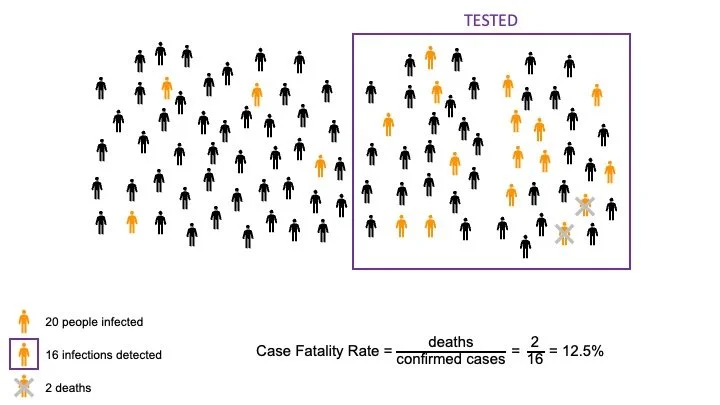

To illustrate this potential bias, consider the following scenarios:

1. In a population of 100 people, 20 people are infected. Only a quarter of the population gets tested, mostly the people who feel really sick, and 10 cases are detected. Two of those cases prove to be fatal. The CFR is 20%.

2. In a similar population of 100 people, 20 of whom are infected, testing is more common. In this scenario, half of the population gets tested, including people who don’t feel so sick. Now, 16 cases are detected. There are still 2 fatal cases, but here the CFR is 12.5%.

In our article, we examined how this potential bias caused by testing rates impacts the COVID-19 CFRs that are observed among women and men. We analyzed sex-disaggregated COVID-19 testing, case, and death data from the three states for which these data are available: Illinois, Indiana, and Minnesota (the Indiana data portal was active at the time of analysis but is no longer active). In all three states, women are tested more often than men. In our paper, we discuss some likely reasons why this is the case, including frequent testing among healthcare workers (who are disproportionately women) and pregnant people, and generally higher health care seeking behaviors among women -- all of these make it likely that more cases, especially mild and asymptomatic cases, will be detected in women than in men. That is, men are more like scenario 1 above, and women are more like scenario 2.

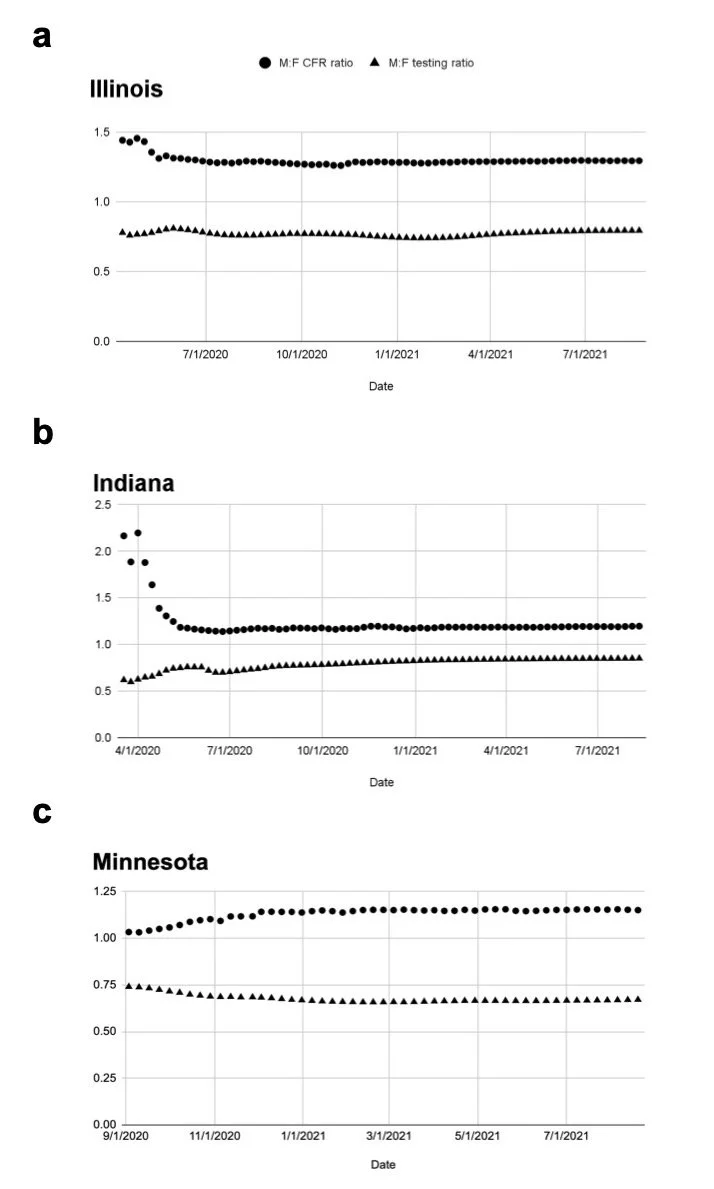

When we graphed the testing ratio (tests among men compared to women) and CFR ratio (CFR in men compared to women) over time in each of the states, we found a striking visual pattern -- testing skew and CFR ratio are inversely related. That is, the more disparate testing is between men and women, the greater the observed sex disparity in CFR. When testing is more similar by sex, CFRs are more similar.

Cumulative testing ratio and CFR ratio by state over time. Reproduced from Gompers et al. 2021.

Key take-homes and recommendations

The significant predictive relationship between testing skew and CFR ratio means that CFRs by themselves are not a sufficient metric for demonstrating sex disparities (in COVID-19 or other scenarios when case rates might vary by gender/sex due to social contextual factors). Widespread lower testing in men compared to women artificially inflates the CFR in men, since fewer cases (especially mild and asymptomatic cases) are likely to be detected in men. This doesn’t mean that there are no sex differences in COVID-19 outcomes, just that CFRs are limited in their ability to establish sex differences. In our commentary, we put forth several suggestions for how to ameliorate the issue of CFRs’ limited validity, including:

Any dashboard or publication that reports CFRs by sex should note the possibility of testing skew, and ideally, sex-disaggregated data on testing should be presented alongside CFR data.

Dashboards and publications should also be clear about whether data is disaggregated by sex assigned at birth or by gender identity. The data used in this analysis were not clear on this distinction, reflecting a wider problem in COVID-19 and public health data reporting that limits our ability to distinguish the separate and overlapping effects of gender and sex on health outcomes, as well as completely prevents any study of the toll of the pandemic on transgender and nonbinary communities.

Beyond gender/sex, sociodemographic variables including race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, occupation, and comorbidity should also be collected and reported, ideally with some variables reported in interaction with gender/sex. These variables are crucial to understanding with more accuracy where COVID-19 testing and outcome disparities lie.

“The significant predictive relationship between testing skew and CFR ratio means that CFRs by themselves are not a sufficient metric for demonstrating sex disparities”

Diving into methods: how we did the analysis

For those interested, here is a deeper dive into the data and analyses conducted than the space allowed for in our Women’s Health Issues commentary.

Sex-disaggregated COVID-19 testing data are available in Illinois beginning April 12, 2020. At the first available time point, a total of 119,015 COVID-19 tests had been conducted. Of these, 43.8% (52,085) were among men and 56.2% (66,930) among women, for a M:F testing ratio of 0.78. This indicates greater testing among women in Illinois, as the state population is 49.1% male and 50.9% female. The CFR was 4.14% among men (415 deaths / 10,026 cases) and 2.87% among women (302 deaths / 10,507 cases), yielding a M:F CFR ratio of 1.44. Both the testing and CFR ratios remained relatively stable over the course of the pandemic. As of August 22, 2021, the M:F testing ratio was 0.79 (11,499,051 male and 14,507,775 female tests). While the CFR was lower for both men (12,869 deaths / 702,865 cases; 1.83% CFR) and women (10,885 deaths / 768,584 cases; 1.42% CFR) by this time, the M:F CFR ratio was similar to the start of the pandemic, at 1.29.

In Indiana, COVID-19 testing data are available by sex starting February 26, 2020. Due to very small numbers of cases and deaths for the first several weeks of data, cumulative M:F testing ratio and CFR ratio in Indiana by week are presented beginning March 25, 2020. On that date, the M:F testing ratio was 0.62, with 38.3% of tests (4,085 / 10,674) conducted among men and 61.7% (6,589 / 10,674) among women. Again, this is substantially skewed from the overall population of the state, which is 49.3% male and 50.7% female. The male CFR was 7.80% (17 deaths / 217 cases) and the female CFR was 3.60% (9 deaths / 250 cases), yielding a M:F CFR ratio of 2.17. (There were still few cases and deaths in Indiana in March 2020, which is why these numbers are smaller than the first data points available for Illinois and Minnesota.) Over time, the M:F testing ratio increased and grew closer to 1, representing more equal testing among men and women, and the CFR ratio decreased and fell closer to 1, indicating more similar fatality rates by sex. By August 18, 2021, the M:F testing ratio was 0.85 (1,732,076 male / 2,035,788 female tests). Cumulative CFR was substantially lower and more similar in both groups compared to the beginning of the pandemic: 1.87% among men (6,993 deaths / 374,173 cases) and 1.56% among women (6,669 deaths / 426,986 cases), yielding a M:F CFR ratio of 1.20.

Minnesota began reporting COVID-19 testing data by sex on September 3, 2020 (retroactively including all tests, cases, and deaths that had occurred in previous months). By that time, 1,517,571 tests had been conducted, of which 42.5% (645,537) were among men and 57.5% (872,034) were among women, for a M:F testing ratio of 0.74. By comparison, the population of Minnesota is 49.7% male and 50.3% female. Fatality was almost equal between men and women: the M:F CFR was 1.03, with a 2.41% CFR in men (903 deaths / 37,513 cases) and 2.33% in women (933 deaths / 40,063 cases). Over the ensuing months, the M:F testing ratio fell further below 1, indicating a shrinking proportion of tests being conducted among men. By August 19, 2021, 40.2% (4,318,272) of 10,752,783 total tests were conducted among men and 59.8% (6,434,511) were among women, yielding a testing ratio of 0.67. During this time, the CFR ratio rose above 1, indicating more disparate fatality rates by sex. The CFR ratio reached a value of 1.15 at the end of the time period, with a CFR of 1.32% (4,048 deaths / 306,769 cases) among men and 1.15% (3,686 deaths / 321,593 cases) among women.

We performed a linear mixed-effects model to test the association between M:F testing ratio and M:F CFR (outcome variable), conditional on month-year (continuous variable) and included random intercepts for the state. The model confirmed the inverse relationship between M:F testing ratio and M:F CFR ratio -- the coefficient for the estimate of M:F testing ratio on M:F CFR was -1.65 (95% CI: -2.13, -1.18; P < 0.001).

How to Cite this Blog Post

Gompers, A. “Explainer: The Limitations of Case Fatality Rates for Measuring Sex Disparities.” GenderSci Blog, 12 Jan. 2022. genderscilab.org/blog/case-fatality-rates-limitations-explainer

Statement of Intellectual Labor:

Annika Gompers wrote the blog post based on the GenderSci Lab’s commentary authored by Annika Gompers, Joseph Bruch, and Sarah Richardson. Sarah Richardson, Kelsey Ichikawa, Joseph Bruch, and Heather Shattuck-Heidorn edited the post.